The successive rate hikes by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), considered its most aggressive cycle in many years, have resulted in the emergence of the fixed-rate cliff for many borrowers.

How borrowers end up in the face of a fixed-rate cliff

It all started with the dramatic fall in the cash rate during the pandemic, hitting the historic low of 0.10% in November 2020.

Based on the available data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, banks financed around 1.2 million new home loans between January 2020 to October 2021, at a time when fixed rates were falling.

It is crucial to take note that between July and August 2021, fixed-term home lending surged to 46% of new mortgage commitments, significantly high than the historic share of 15%.

By October in the same year, the RBA’s financial stability review noted that around 35% of outstanding loans was on fixed terms, including those with split loans.

More importantly, the RBA noted that two-thirds of the loans under fixed terms are due to expire in 2023.

CoreLogic head of research Eliza Owen said the cliff would mean fixed-rate borrowers are going to be repriced at a significantly higher rate.

“When fixed terms come to an end, borrowers will need to refinance their loan — factoring in another 50 basis points of rate hikes over March and April, average variable rates could be around 5.7% for owner-occupiers and over 6.0% for investors,” she said.

But should this be a cause of concern? Ms Owen shares five important things borrowers must know about this fixed-rate cliff:

1. Impacts will start to intensify in April.

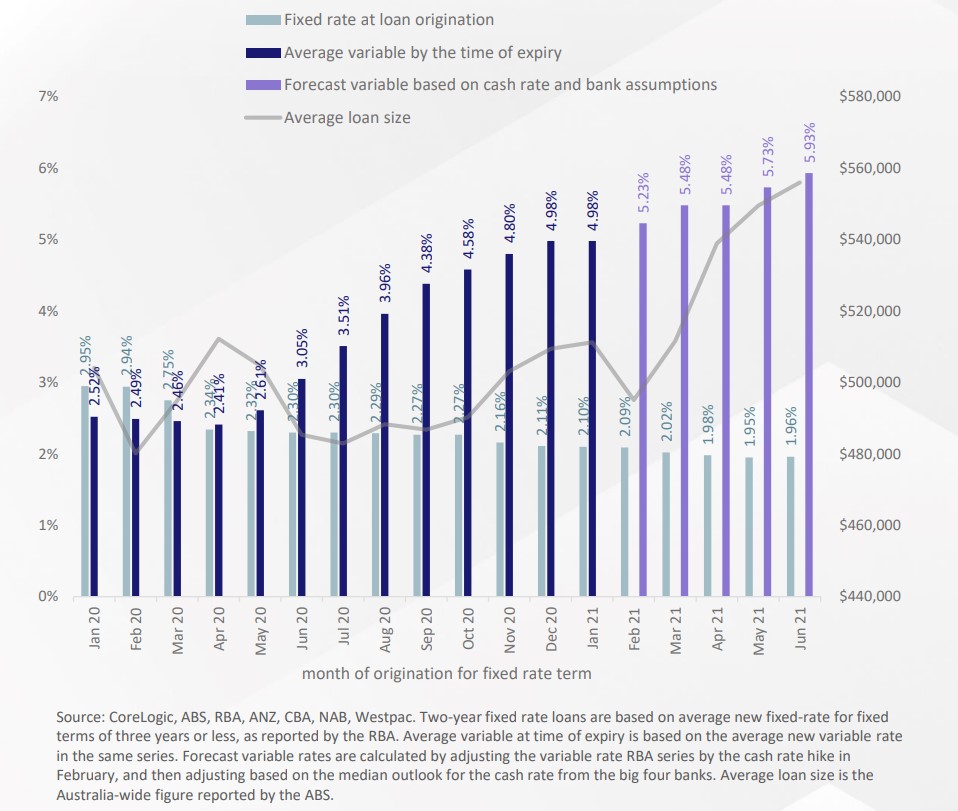

The CoreLogic chart below shows how intense the initial repricing from an average two-year fixed term rate during the pandemic to a variable rate two years later.

“Not only will the change in rates be stark for expiring fixed terms this year because of more rate rises, but average loan sizes also grew notably from April 2021 during the housing boom,” Ms Owen said.

Based on the projections, the average loan size of $538,936 taken out in April 2021 at a fixed rate of 1.98% would end up with a 5.48% variable rate when it rolls over in April 2023.

The rate hike would mean that the monthly repayment of $1,986.63 would now balloon to $3,053.26.

Ms Owen said the rate hikes would produce challenges in terms of serviceability, especially as interest rates already rose beyond the 3 percentage point minimum buffer set by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority.

“Stretched serviceability could be compounded by an increase in the unemployment rate this year along with higher than budgeted household costs due to high inflation,” she said.

“A rise in distressed sales could also put added downward pressure on property values — if people are forced to sell their home in a declining market, there is the added risk of being unable to recover mortgage debt from the sale of a home.”

2. Variable rate borrowers have already faced steep rate hikes.

Between April 2022 and December 2022, the average outstanding variable mortgage rates increased 263bps while the cash rate went up 300bps during the same time.

Based on average factors, a variable-rate loan taken in April 2022 would have seen mortgage repayments rise $935 per month by the end of the year.

“In other words, the majority of outstanding mortgage debt has already been subject to steep rate rises. And yet, housing market measures show resilience in mortgaged households,” she said.

In fact, looking at the volume of new advertised properties hitting the market for sale nationally, the figure remains largely contained, hitting 14.8% below the previous five-year average.

Another thing to look at is the trend in offset and redraw account contributions — while they have declined from the pre-pandemic average of 20.1%, the level remained high at 15.7% as of December.

This begs the question, will fixed-rate borrowers be able to cope with the rate hikes just as much as variable-rate holders?

Citing the RBA’s Financial Stability Review published in October last year, Ms Owen said the current cohort of fixed-rate borrowers have a similar income to variable rate holders, which means that they should be able to save the same way variable borrowers have done.

“Borrowers that rolled onto variable rates quickly transferred large savings into offset and redraw accounts. This suggests that fixed-rate borrowers have also been stowing money away, even if they haven’t had the offset and redraw facilities to put those savings into,” she said.

3. What comes up, must go down… even mortgage rates.

While there are chances of further rate rises, their economic impacts might ultimately lead to a change in tone as the year progresses.

In fact, some economists are predicting the cash rate to start easing again later this year.

“Borrowers may be better positioned to seek a lower interest rate as the cash rate passes a peak, which some believe could be as soon as late 2023,” Ms Owen said.

“This means while increased variable rates could create tough conditions for households in the short term, the steep hike in interest repayments will not be for the entire life of the loan.”

Furthermore, refinancing is at the highest levels, which means that banks are more incentivised to provide attractive offers to stay competitive.

4. Most markets are able to retain high equity.

While the rate rises increases the risk of households falling into arears, the substantial gains in house prices over the past few years would mean that only a small share of borrowers might not be able to pay off their debt with the sale of their home.

CoreLogic Figures show that while the decline in housing markets from respective peaks are varied, only around 2.9% of suburbs across the country have seen home values fall more than 20%.

“Large deposits also help to strengthen the equity position of mortgage holders,” Ms Owen said.

“Around 0.5% of home loans were in negative equity amid current price falls. If home values were to fall a further 10%, the RBA estimates the rate of loans in negative equity would only rise to around 1%.”

5. It will take time to see an impact.

Despite all these seemingly positive signs, however, it is still crucial to know the ongoing risks given the lagging impacts of the rate rises.

According to the latest data available from APRA, only 1% of home loans were non-performing in September — these refer to home loans that are at least 30 days past due.

“Understanding the impact of rising rates on some households is difficult, because different income cohorts and support networks will vary in their response to higher interest costs,” Ms Owen said.

“For example, some people may be able to move in with parents and rent out their home to supplement mortgage payments. People on higher incomes can also generally expend a higher portion of their income on housing.”

-

Photo by Shaan Johari from Pexels.

Collections: Mortgage News Interest Rates

Share