While many Australians are likely to fall behind their mortgage repayments in the coming months, there is still no reason to worry about rising home-loan arrears, an official from the Reserve Bank of Australia said.

Arrears have been increasing annually over the recent years and are currently at their highest level since 2010, but RBA head for financial stability Jonathan Kearns said this should not pose any risks to the economy.

"With overall strong lending standards, so long as unemployment remains low, arrears rates should not rise to levels that pose a risk to the financial system or cause great harm to the household sector," he said.

Kearns said the majority of housing loans are still on track, with many borrowers still being able to have prepayment buffers on their mortgages.

"Around two-thirds of borrowers have accumulated buffers of prepayments of their mortgage, and some others have other assets outside of their property," he said, adding that these households would be able to withstand some period of unemployment.

However, he said should unemployment extend too long and deplete their savings, these households could risk falling into arrears.

Global home-loan arrears trend

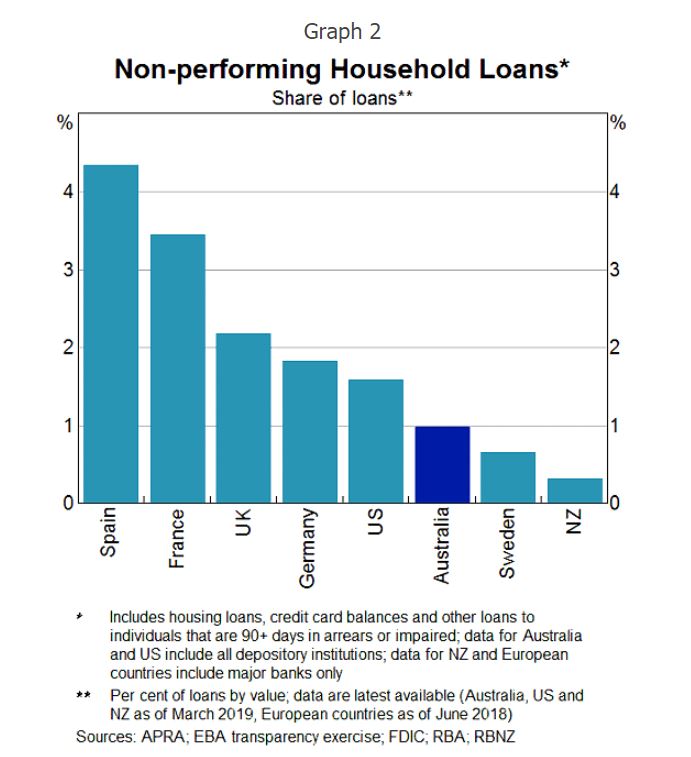

Australian arrears are relatively lower than those in many advanced economies. Spain, France, the UK, Germany, and the US all have a higher share of non-performing loans. The graph below shows how arrears in Australia compare to other countries:

"Another way to look at the arrears rate in Australia is to note that over 99% of housing loans are on, or ahead of, schedule. Making loans involves risk, and banks are used to managing this risk. If the arrears rate was persistently very low, that would suggest that lenders were being too cautious in lending," Kearns said.

What's driving arrears?

Kearns said it could be surprising that arrears are rising despite the growth in employment and the decline in unemployment.

"What we can see across Australia is there is a clear pattern of more loans going into arrears in locations where the unemployment rate is higher," he said.

"People aged in their thirties and forties are more likely to have a mortgage, particularly if they have good employment prospects. So, if more of them become unemployed, arrears rates will rise," he said. "Conversely, if it is older or younger workers who get a job, but don't have a mortgage, or second income earners in households already comfortably making their repayments, this won't lead to a decline in arrears rates."

Given this, he said it is not reliable to just depend on unemployment to predict where arrears would go — the growth of income also plays a huge role in the movement of arrears.

"When nominal income is rising strongly, over time, mortgage payments take up a declining share of a borrower's income. As their mortgage ages and their income rises, borrowers are better placed to withstand a fall in their income or rise in expenses," he said.

The problem with Australia, however, is that the nominal income growth has been around half its longer-run average over the past five years.

"Rising income hasn't been able to compensate for other factors that might cause households to struggle to make their mortgage repayments," he said.

Collections: Mortgage News

Share